In my continuing quest to (not actually) deliver a perfect lemon to the vicereines of Østgarðr (see also, and also), I cast around for a reasonably-simple period-esque project and found the inspiration right at my doorstep, in the bounty of my sidewalk garden.

Lemon balm is a citrus-scented member of the mint family, which grows in profusion in the bevy of containers that are home to my tiny greenspace — in fact, it grows so aggressively that I need to cut it back frequently to keep it from crowding out the other showier plants, and it was while I was trimming it that I realized I could put it to a productive use.

I know that mint is frequently used as a flavoring in sekanjabin, a sweet-and-sour syrup widely consumed as a beverage within the SCA with Persian origins and with precedents found across much of the ancient and medieval world, and it seemed reasonable to me that lemon balm might be used in the same way. Indeed, since oxymel (as sekanjabin-style syrups are called in some cultures) is often considered medicinal, and lemon balm was considered a medicinal plant, the combination seemed natural. (Lemon balm’s soothing effects are not just a medieval fantasy, but have been confirmed by modern studies.)

Research

I headed to my desk to do some online research, consulting a range of standard documents as well as prior work in this area by Aneleda Falconbridge, Giata Magdalena Alberti, Thomasina Coke, and Cariadoc of the Bow; I am grateful to each of these individuals for paving the way.

Although flavored oxymels are known to be period, and I was able to find modern recipes and preparations of lemon-balm oxymel, my casual investigation didn’t turn up any period recipes for exactly what I had in mind — indeed, even Master Cariadoc was unable to find a period recipe for the ubiquitous mint sekanjabin, relying instead on a thirteenth-century Andalusian source that includes only vinegar and sugar — but I decided to forge on undaunted.

(There is extensive documentation for a medieval lemon-balm beverage preparation in the form of Carmelite water, but that calls for wine as the carrier rather than a syrup, and the site at which I was to make this presentation had made clear that absolutely no alcohol was allowed in any form, so I filed this away as an idea for another time.)

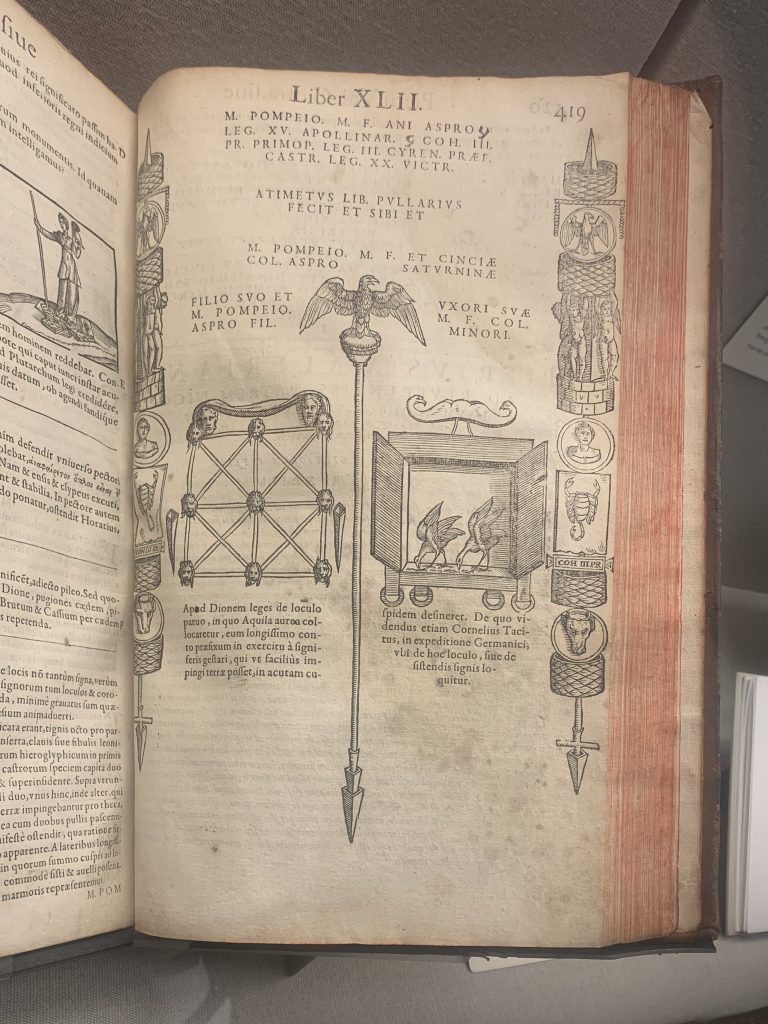

For the base proportions of the oxymel, I followed the advice of Bald’s Leechbook, an Anglo-Saxon medical text written circa 1040 CE. Because the British Library’s digital edition of the surviving manuscript was knocked offline by a cyber attack more than six months ago, I relied on a Victorian reprint which provides a transcription and translation:

Take of vinegar, one part; of honey, well cleansed, two parts; of water, the fourth part; then seethe down to the third or fourth part of the liquid, and skim the foam and the refuse off continually, until the mixture be fully sodden.

Leechdoms, Wortcunning, and Starcraft of Early England, by Thomas Oswald Cockayne, 1864, page 287.

With this information under my belt, I set to work.

Procedure

I harvested a couple dozen stalks of lemon balm from my garden, clipping the stems above a remaining leaf node to allow the plant to regrow.

Then I prepared my oxymel base, using three cups of raw honey, one and a half cups of apple cider vinegar, and one and a half cups of water. I added these to a tinned pot and gently brought them to a low simmer to begin reducing.

After some time had passed and the syrup had begun reducing in volume, I removed the main stems from the lemon balm, washed the leaves in a few changes of fresh water, and roughly chopped them to encourage the release of their oils, then added them to the pot.

Lastly I added a few subsidiary flavor notes in the form of a small amount of lime zest and a pinch of freshly-ground nutmeg, and allowed the entire concoction to simmer for a just little while longer, stopping when it had reduced in volume by half.

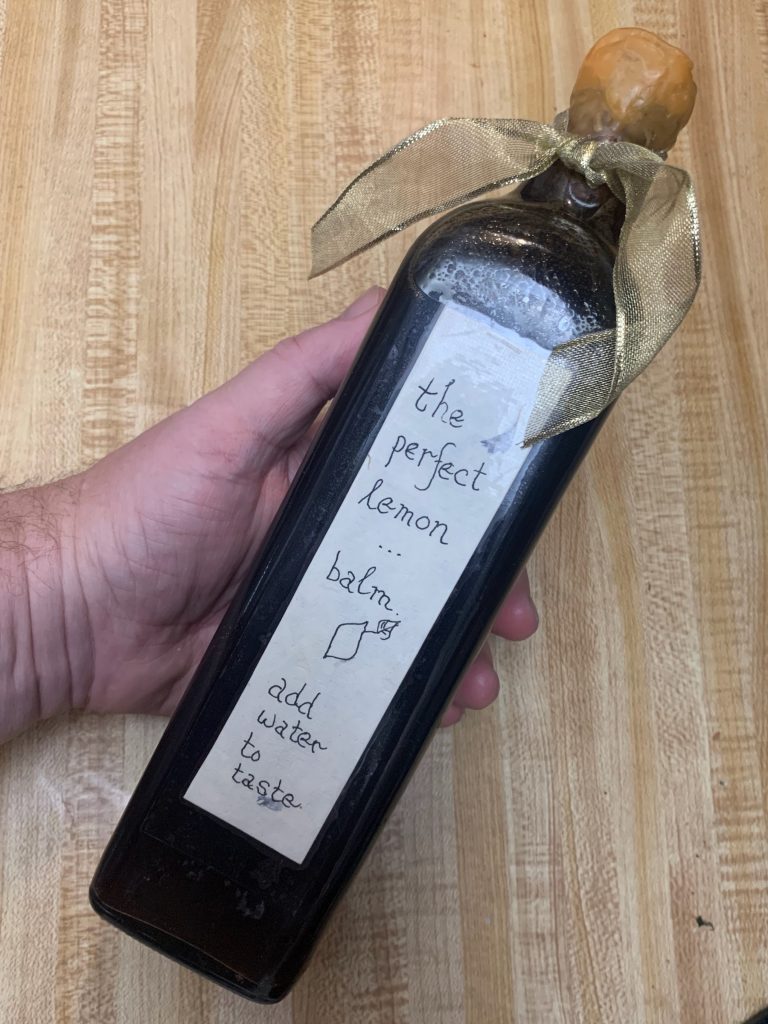

After tasting a sample (diluted with ice) to ensure it hadn’t all gone horribly wrong, I allowed it to cool and then passed it through a sieve, pressing the sodden leaves to extract their remaining elixir. Finally I transferred it in a glass bottle and corked it; then, uncertain as to whether the cork would hold, I waxed the top of the bottle for a bit of extra protection, and requested a descriptive label from the nearest scribe — thanks Alienor!

Typically sekanjabin or oxymel is diluted by about 1:8 in water to drink as a refreshing beverage, although the exact proportions are flexible and folks are encouraged to adjust the ratio to their taste. It can also be drunk warm, or the syrup can be added to other recipes or cocktails anywhere you’d like a sweet, tangy burst of flavor.

Presentation

I presented this bottle to the vicereines at the Lions Learn Lessons schola, and although they seemed well pleased with the gift, as required by the structure of the shtick they decided that this was not quite what they had in mind, and sent me out to try again.

Here is my script for the presentation:

For the curious, below are the sources for the period descriptions of lemon balm’s medicinal uses mentioned above; although these phrases are widely repeated in modern writing about the herb as if they were direct quotes from historical documents, it’s surprisingly difficult to trace them to actual period sources and they are almost certainly paraphrases by later secondary sources.

- “Sweetens the spirit”: commonly credited to Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, 70 CE, although not present in this translation.

- “Makes the heart merry and joyful”: commonly credited to Ibn Sina, Canon of Medicine, 1025 CE; found in John Gerard, The Herbal, or General History of Plants, 1597 CE.

- “[Cures] all complaints [of] a disordered state of the nervous system”: commonly credited to Paracelsus, early 1500s; found in Sophia Emma Magdalene Grieve, Modern Herbal, 1931 CE.